Introduction

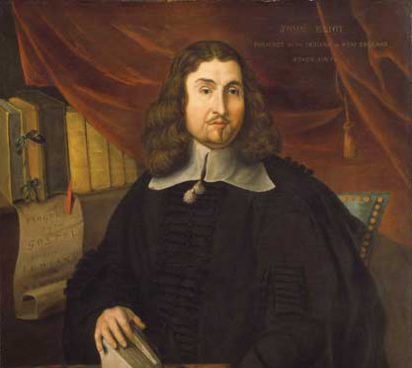

John Eliot was a not a typical missionary, in terms of how we would normally view missionaries today. He was never formally sent by a mission board. It was not his main calling, which was as pastor in Roxbury, New England, but he certainly was a missionary to the Native American Indian tribes in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He felt the need to reach those people so often overlooked by most of the people who arrived in Massachusetts during the 16th century. He laboured as a man with a huge burden to reach those people, while also labouring full-time in his pastorate in Roxbury, where he served faithfully for roughly 58 years.

An extraordinary task as these Indians typically did not understand or speak any English. They were uncivilized and wild in the eyes of the English settlers. They were at times even seen as “savages” by the English. No written form of Indian Algonquian language existed. There were no lexicons or no grammars to work from for this missionary work. Culturally and religiously, the English settlers, which included Eliot, could not have been more different from their new native neighbours.

Eliot did not leave behind him a wealth of academic theological treatises, which is why he is not viewed as an academic or a scholar by many, but he went on to do something extraordinary in reaching the Indians for Christ. He poured his life into this effort which was often unpopular and lacked widespread major support. Eliot, in many ways, was a man before his time in terms of the missionary work which would follow in the 19th century.

Early Life

John Eliot was born in Widford, Hertfordshire in England, probably in year 1604. There is a record of him being baptized in 1604 on August 5th, so considering this it is most likely the year he was also born in, as children were typically baptized quiet close to when they were born. Eliot grew up in a village called Nazeing, which is a village and parish in Essex, near the east coast of England. This was a part of Eliot’s life would prove significant later as it greatly influenced him in where he would be a pastor for 58 years in New England. This was because many from Nazeing would eventually follow Eliot and settle in Roxbury, New England.

Little is known of Eliot’s family life when he was young, but he did make this comment of his upbringing in the Christian faith at his home in Nazeing:

“Here the Lord said unto my dead soul, live! live! and through the grace of God I do live forever! When I came to this blessed family I then saw as never before the power of godliness in its lively vigour and efficacy.”[1]

From the available evidence, it seems that John was raised in a godly pious home where he was instructed in godly learning. He progressed to a grammar school, probably around the age of 6, where education was theological in focus. The Bible, prayer and doctrine were a major part of the education in the village of Nazeing. Catechism was also very common, which helped Eliot to develop the convictions which made life in England very difficult for him and others in Nazeing. These theological convictions, of non-conformity with the ritualism of the then Church of England, would also lead to him finding a new home in the New World.

Grammar school seems to have gone well as he progressed to study at Jesus College in Cambridge University in 1618. There he would have come under the influence of the then master of the college, Roger Andrewes, who had been one of the translators of the King James translation of the Bible. As Eliot developed, it became increasingly apparent that he would not be able to preach in England with his theological convictions due to the reign of King Charles I. With the growing influence on the English crown by William Laud, who would later become Archbishop Laud in 1633, it became clear to Eliot and many other non-conformists that it was not safe to stay in England. Many others left England for New England for similar reasons.

The New World and New England

It was an exciting time of exploration, but many who left England to go to New England did so out of religious convictions. Many of them where Puritans who believed that they could not in good conscience submit to the ritualism of the Church of England. Once the door began to close by the tyrannical arm of King Charles I, many made their way to the New World on ships, which led to the founding of various towns in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and in the Plymouth Colony. There was a desire among many who travelled that they would worship God in a way pleasing before him.

Of course, these new settlers, of which Eliot was one, were not alone. There were a number of various tribes of natives who were living in the area. Relations were largely peaceful in the early days, but the new settlers brought many diseases to the New World. A series of epidemics drastically killed off many Indians who had no immunity to these infections coming from Europe. This lead to these new settlers, through this unfortunate occurrence and through hard work, taking over large areas of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Ministry and Family Life at Roxbury

John Eliot arrived in New England in 1631 aboard the Lyon ship following a ten-week voyage. On arrival, Eliot took up residence in Boston where he would serve as a substitute minister until the church’s then minister returned from England. Once the church’s minister returned, the minister in question was John Wilson, the congregation offered to have Eliot also remain on as a teacher there. However, by this time, a group had arrived in nearby Roxbury from his home village Nazeing and they were seeking a minister of their own. Due to this development, not due to any dissatisfaction with the Boston congregation, he refused the call in Boston but accepted one from the newly formed church in Roxbury where Eliot would be their first minister. These people from Nazeing were his friends and neighbours, making it very difficult for him to not be with them and minister to them. He also had promised to his friends in England, before setting sail for New England, that he would be their pastor if he was still available when they all came over. With them he would remain their pastor for another 58 years.

Eliot’s then wife to be arrived in 1632, whose name was Hanna Mumford. They married in October 1632 and it was the first wedding in the town of Roxbury. Not a lot is known about Eliot’s wife, but she had a reputation of being a wonderful and warm host, who was known for her hospitality. Hanna and John had 6 children, five sons and one daughter.

It’s also worth noting early in Eliot’s ministry that he was involved in the now famous Antinomian Controversy involving Anne Hutchison, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, which took place between 1636 and 1638. It was a case over Anne Hutchison’s teaching and her unorthodox view of God’s grace. These charges included the rejection of the doctrine of the resurrection from the dead. Today, Hutchison is seen as some heroine of religious liberty, but in the 17th century she was seen as a danger to the commonwealth. Eliot was involved in her condemnation and cross examination, and she was eventually exiled from the colony. The controversy took place before both church and magistrate assemblies. Eliot made these comments on the Hutchinson case:

“We are altogether unsatisfied with her answer & we thinke it is very dangerous to dispute this Question [of the resurrection] so longe in the Congregation … we much feare her spirit.”[2]

On the controversy, Ola Elizabeth Winslow made the following comment on Eliot’s role during the proceedings:

“In this early Boston religious crisis John Eliot had put himself on record as a champion of orthodoxy. His witness against Anne Hutchinson had confirmed in him loyalties that would be lifelong.”[3]

However, Eliot was not one to be typically drawn into controversy. He had a tender love for the people to whom he ministered to. He had a deep sympathy for the people under his care, even in cases of excommunication. He was not a man who neglected his duties in his church as there was a great love and connection with his people, even though he devoted so much time to a people the new settlers did not yet fully understand.

Eliot’s Heart to Reach the Indian People

It is not clear when John Eliot’s interest in reaching the Indians began, though there is some evidence of others working to reach the Indians in other parts of New England, but nothing comes close to that of Eliot in reaching the Indian population. It would earn him the nickname “the Apostle to the Indians”. The Indians were viewed as barbarous and uncivilized. Many believed that they were too wild to be reached with the gospel and many wondered if they could ever be converted. The style of dress of Indians was radically different, as with hair styles. Indian children would be half naked and this was all very strange to the New England settlers. For these reasons and growing mistrust that took place between white English settlers and the Indians, the work was never very popular.

One difficulty between the new settlers and the Indians was the use of land. The Indians viewed land very differently from the English settlers. Indians had their own land but tended to roam around a lot hunting for food, while the settlers from England typically did not want trespassing on their land. This was strange for the Indian population. As time went on, with the effects of disease outbreaks from these new European settlers, and with the growth of more land owned by the English, the Indians felt more and more penned in. There was a sense in which they began to feel trapped, not able to carry on as they once did. These cultural differences with land are important, as they would form one of the major reasons for King Philip’s War (1675-1678), which took place between the Indians and white men. It was also one of the issues John Eliot tried to resolve in starting towns where Indians, converted to Christianity, could inhabit. Eliot showed in this effort that he cared so deeply for the Indians that he was willing take all these factors into account, without sacrificing the truth.

The Indian Language (Algonquian)

We have mentioned the cultural difficulties in reaching out to the Indians, and the English reluctance to do so, but there was also the issue of the Indian language. Without the language, any mission work with the Indians would be futile as nothing would be understood. The language of the Indians in that area was called Algonquian. There was no written form of the language. There was no grammar, no lexicon and many of the Indians did not speak English. Often, there were words used in our English Bibles but Algonquian simply had no corresponding term to use.

How could this be done? Many suggested making the Indians just like the English settlers, but Eliot disapproved of this and sought to reach them where they were at. Eliot wanted to preach to them in their own language and then produce the Bible in the language. Very few thought it was possible or that Eliot was capable of such a task.

On the great difficulty of the language itself, Cotton Mather made this comment:

“If their alphabet be short, I am sure the words composed by it, are long enough to tire the patience of any scholar in the world. One would thing they had been growing ever since Babel, into the dimensions to which they are now extended: if I must translate ‘our loves,’ it must be ‘Noowomantainmoonkamnownash.’ I pray you count the letters.”[4]

Eliot’s Passion for Education

Before we look at what Eliot did to bridge this gap and overcome this hurdle with the Indians, let us look at how highly he viewed education. It is this high regard which shaped how he approach the Indians.

Eliot founded the first Sabbath School in the New World. He saw the major importance of catechizing the young people, forming schools and equipping teachers. He was afraid that young people would be distracted by the new settlement, rather than given to learning and prayer. Eliot made plans for founding schools and prayed for good schools in various areas. During a synod meeting of the churches in New England he said:

“Lord for schools everywhere among us! That our schools may flourish! That every member of this assembly may go home and procure a good school to be encouraged in the town in which he lives.”[5]

Eliot founded the Roxbury Latin School in 1645, which was around the time he was learning the Indian language to reach the Indian people. Eliot’s endeavors in order to the founding of schools and promoting their growth, led to great fruit coming from them. As Mather wrote:

“God so blessed his endeavors that Roxbury could not live quietly without a free school in the town, and the same issue of it has been one thing which has almost made me put the title of schola illustris upon that little nursery; that is, that Roxbury has afforded more scholars, first for the college, and then for the public, than any town of its bigness, or if I mistake not, of twice its bigness in all New England.”[6]

He took every opportunity to educate young people, which led him across the path of Indians whom he wished to educate. While teaching them he saw an opportunity to be educated himself and learn the Indian language. In 1643 he began to study the Indian language through a young Indian servant who worked in an English home. He was bright and Eliot saw an opportunity to learn from this servant, whose name was Cockenoe. Eliot would help the young servant to learn to write himself, although he was well versed in English and the Indian language in the area. Eliot had written years earlier how he hoped and expected that the Indians would be reached for Christ. This burden grew to the point where he now wanted to do it himself.

Public Ministry to the Indians

Eliot began to preach to the Indians in 1646 after making much progress in those three years in the Indian language. The first sermon took place on October 28th of that year. He began a public preaching ministry there using their language and used the wigwam of Waban the chief for his outreach. Waban was part of the Nipmuc group and his wigwam was found in Nonantum, Massachusetts. A wigwam was a type of dome shaped hut or tent which the Indian’s had. These were “hopeful beginnings”, as John Winthrop called the first sermons preached to the Indians, as some hoped this might lead to better relations with the Indians and conversions to the Christian faith. These “hopeful beginnings” began over 40 years of labour to the Indian people on behalf of Eliot.

When Eliot stepped forward to preach, he began with prayer in English. He dared not address God with his heart using the Algonquian language. Eliot, while at the wigwam, preached on “Prophesy unto the wind” from Ezekiel. This might not seem significant to us, but the name Waban meant “wind”. Here we see Eliot trying, without compromising, to meet people where they were at. He also went through the Ten Commandments, giving instruction on what each of the commandments meant. His love for educating young children came to the fore when he would catechize the Indian children with three questions from the catechism. The questions would include such questions as “Who made you and all the world?” with the answer being “God”. These questions with answers were repeated a number of times, and then the children were directed repeat in chorus. All this was done in their own native tongue.

Eliot was not naïve as he knew it would take a long time for some of these concepts to bed in. As evidence from later professions of faith from the Indians, one of the doctrines the Indians struggled with was that of original sin, as they had no concept of it in their background. It would take careful and constant teaching over some years, as the concepts presented by Eliot would easily be misunderstood. In an Indian context there were many gods, some good and some bad. The danger was if they were rushed into churches without a credible profession of faith, they would fuse these concepts with their pagan ones. The people at Waban’s wigwam continued to listen and Eliot was ever willing to teach.

Indian Religious Belief

The Indians had many myths and legends about creation. Eliot taught the Indians about how God created the world and the heavens in six days. They listened attentively but there was an attempt among some to blend the best of their beliefs with that of Christianity. It was important for missionary efforts that the Indians knew the difference between their myths and legends, and the truth itself. Which was a difficult task given that their religion, if one is to use that term, was not at all theological. They had a nebulous belief in the power of the unseen forces. They believed in the power of devils, witches, good spirits and evil spirits. They believed these powers were found in places and objects, and so there was danger in them. This is why they performed ceremonial acts to ward away the danger of such forces. For them Christianity was just the religion of another tribe. There were gods or deities, both good and evil, but these did not punish for sin. That was the role of the family or tribe to perform.

So the concept of a god who must be obeyed, or something akin to the Ten Commandments was unknown in an Indian context. Much groundwork was needed so that these people could understand the gospel at all. The concept of the God, who created Heaven and Earth, who poured out His wrath in Hell would have to be taught to them. The righteous standard of the law needed to be taught to them, otherwise any conversions may be purely adding another deity to their collection.

So these were stony hearts Eliot was meeting as he made repeated trips to Waban’s wigwam. They needed to see that they were sinners in need of God’s mercy. They were asked if they kept the law of God, as summarized in the Ten Commandments. They were told if they didn’t then God was angry with this, but these truths were given with much affection and love. Questions of Sabbath observance came up and how this commandment was to be kept. The more and more the Indians saw how far short they fell of the glory of God, the more the Spirit of God worked in their heart.

One of the questions which came from those Indians to Eliot was: “Why has no white man ever told us this before? Many years ago white men came. Why did you wait to tell us?”[7] Which must have been heartbreaking for Eliot to hear, but there was no answer. He simply said “I am sorry.”

Let us pause for a second and ponder this. For some time much of the church didn’t believe that the Indians could be reached. They saw them as savages who could not be tamed. There were those who wanted to reach the Indians outside of Eliot, but only a small few. Of course the language was a challenge, but it makes us wonder who are we, in our day, overlooking in our evangelism because they may seem too difficult to reach? There are groups, sinners no doubt, but who also need the gospel as much as these Indians who asked this heartbreaking question of “Why did you wait to tell us?”

One of the wonderful aspects of Eliot was he was burdened to reach people, not seeing them as wild savages to be tamed or made to be respectable to English people. He cared deeply about the souls of those Indians. He did not patronize them and he treated them with respect. He also didn’t apologize for the truths he was preaching before them. The message was clear that they must be repent of their sins or face eternal damnation in Hell. Eliot was a Calvinist, but he preached to the Indians plainly, using words and phrases they would understand. Not every word of the Calvinistic Five Points were used, as these Indians were not part of the covenant people at this time. The sermons by Eliot were evangelistic and focused on the fact that “whosoever will” can come to Christ would be saved. Eliot believed in preaching simply to people, as by doing so he would not only reach the scholar, but also the uneducated. This was true both of his ministry in Roxbury which continued on while working with the Indians, but also with the Indians who had a limited exposure to the Christian religion.

Praying Towns

Gradually some of these people were coming to faith in Christ. But what should be done with these new converts? Do they join English churches? As mentioned earlier, the English and the Indians viewed owning land really differently, with the English gradually acquiring more and more land with the Indians felling more and more penned in. The Indians tended to roam around. The English would see them as trespassing on their land. At this moment in time, as Eliot believed, it was not the right or correct to have Indian Christian living side by side with English settlers.

The solution to his issue were what became known as Praying Towns, and the converted Indians themselves who lived there were called Praying Indians. This is not to say that Eliot thought that the Indians did not need to change in terms of modest dress, and even their hair length, but Eliot was patient with these new converts. The establishing of these new towns, beginning with Natick, allowed Indians to form towns where they could continue their way of life on the land while pursuing obedience to Christ in every area of life. If the Indians remained where they were, they would likely lapse back into paganism.

These praying towns were covenanting together before God. John Eliot wrote a work during this period to explain how he believed it would be done in a way which honored God. This work, written in the late 1640s, was entitled “The Christian Commonwealth: or The Civil Policy of the Rising Kingdom of Christ.” This work outlined how these towns were to be organized, largely based upon Jethro’s advice to Moses in Exodus 18. Eliot believed that the Scriptures were to be used in all of life, including state government, so he sought to apply the Scriptures to the Indian’s government of these towns. It was the first book on political theory written on the American continent.

Eliot sought to organize the towns into rulers of various numbers, rulers of ten and of other numbers. Eliot believed at the time of writing that Jethro’s advice to Moses in Exodus 18 was the form of state government found in the scriptures. Alternative views of state government were described as being part of the kingdom of antichrist. This eventually got Eliot into trouble in 1661 with the new court of King Charles II in England. It was not long after the work was published in 1559. However, Eliot retracted his apparent view that this was the only way to govern, as he claimed that any form of government deduced from the Scriptures was of God. This retraction got him out of trouble with the authorities of the day.

There was an attempt in the book, and in the praying towns which followed Eliot, in trying to following the laws of God, both in church and state. The first praying town, Natrick, was very much the template which was followed for the others which followed. 14 praying towns in all were formed in all.

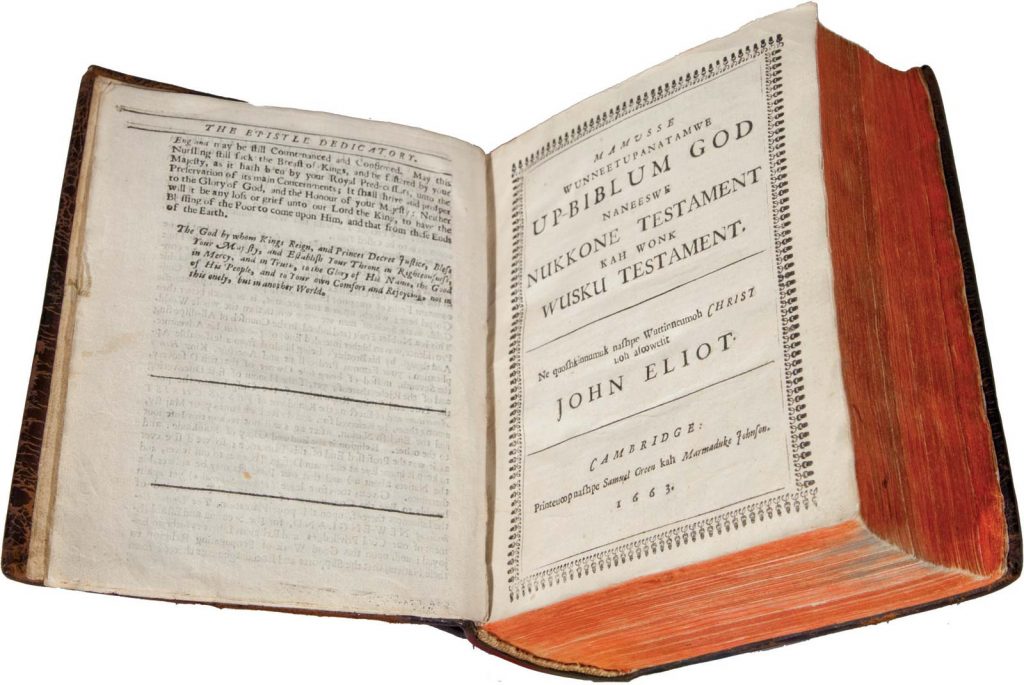

Indian Language Bible

Eliot was eventually successful in translating the Bible into the Indian language. How monumental was the task of translating the Bible into the Indian language? Considering the difficulty of the Indian language, and how it was not a written language, shows how much work was needed to pull this off. A work many saw as impossible. Eliot also produced a lexicon and a grammar for the language. Everything in Eliot’s life was not about a pursuit of scholarly fame, but of doing everything needed to reach these Indian people whom he loved dearly. All this was done while continuing to pastor a flock in Roxbury, which makes his achievement all the more remarkable.

The New Testament was issued in 1661, with the entire Bible coming in 1663. This was the first Bible published on the American continent. The printing of the Bible was made possible by funding from England and the parliament there through The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Sadly, the later war between the Indians and English settlers, called King Philip’s War, would wipe out many of the Indian Bibles in New England. Funding for a second edition was a lot harder to come by because of a growing distrust of the Indians in the region, largely due to the war. However, with the persistence of Eliot, a second edition of the Bible came out in 1685. He was tenacious in his pursuit of educating and sharing the truth of God’s Word with the Indians.

Public Professions of Faith

In Natick, and the other towns founded for the converted Indians, there were newly formed Christian churches. Assemblies were formed of panels who would examine the testimonies of the Indians before allowing them become a member of a congregation. Great care was taken to make sure they understood what it meant to be a Christian. Those who did not have a clear profession of faith which was credible were often rejected. The testimonies would often take a long time to carry out, due to translation and the panel wanted a certain level of detail, at least around 500 words.

Largely, by the end, in the various places these testimonies of faith in Christ were examined. They looked for a rejection of the paganism of their past and an embracing of the Christian faith. Eliot wrote a number of accounts of the testimonies of those who professed faith, including “A Brief Narrative of the Progress of the Gospel Among the Indians of New England” which was written in 1670. Not all of Eliot’s accounts were published.

King Philip’s War

There was a really sad end to many of the Indian towns established. Often Eliot would be let go to preach to the Indians on a Sabbath day, whenever he was able to leave his pulpit in Roxbury. He would travel as much as he could to help the Indians grow and develop. However, many of the praying towns were destroyed due to a conflict which took place between Indians and settlers in the 1670s.

It wasn’t just a setback in terms of the towns, but there was a growing distrust growing between each ethnic group. Indians who converted to Christianity were largely on the side of the English settlers, but this did little to remove the distrust of the Indians as a whole. This distrust didn’t help in terms of finding further funding from England for more Indian Bibles to be printed. This was to replace the ones destroyed in the fighting.

Many of the Indians fell back into sin and some left the faith entirely. One of the reasons given for the abandonment of the faith was the sloth in religious matters when it came to the example given by the English settlers. The Indians were often zealous for the faith, but many of the English were not. This had a negative impact on the Indians.

Eliot’s Legacy

It may look like a tragic end to Eliot’s ministry, but we would sadly miss the blessed legacy left behind by his work. Eliot was thought of extremely fondly by his congregation in Roxbury, a congregation he didn’t neglect in his evangelism of the Indians. He showed what can be done in a life devoted to God and devoted to reaching the lost.

Were there setbacks? Yes, but how many came to Christ through Eliot’s preaching and ministry? Some of these men even went onto to become ministers themselves, who were Indians continuing to work among the Indians. Eliot’s sons became involved in preaching to the Indians near the end of his life. His life and example had a lasting effect.

Eliot was a pioneer and a man before his time. No one, by and large, was doing what he was doing in reaching a people so often overlooked by European settlers. He gave us a blueprint, an imperfect one, to reach a language group with no written language. More than a blueprint, he gave us an example, he showed us himself, of what lengths we should all take to reach those who may be seen as “unworthy” by society with the gospel of saving grace. He showed us what can be done if we don’t give up in that effort. Fruit usually doesn’t come immediately, but lasting fruit did come among all the setbacks along the way. Eliot’s legacy lives on in how we can love those overlooked and forgotten by society.

Bibliography

Ola Elizabeth Winslow, John Eliot “Apostle to the Indians”. [Boston, 1968]

Dustin Benge & Nate Pickowicz, The American Puritans. [Reformation Heritage Books, 2020]

John Eliot, The Christian Commonwealth: or, The Policy of the Rising Kingdom of Jesus Christ. [London, 1659]

James De Normandie, John Eliot the Apostle to the Indians. The Harvard Theological Review, Jul. 1912, Vol. 5, No. 3, Pg. 349-370. [Cambridge University Press]

John Eliot, A Brief Narrative of the Progress of the Gospel Among the Indians of New England, 1670. [Boston, 1868]

J. Patrick Cesarini, John Eliot’s “A Breif History of the Mashepog Indians”, 1666. The William and Mary Quarterly, Jan. 2008, Third Series, Vol. 65, No. 1, Pg. 101-134. [Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture]

[1] James De Normandie, The Harvard Theological Review, Jul. 1912, Vol.5, No. 3, Pg. 349

[2] Ola Elizabeth Winslow, John Eliot: “Apostle to the Indians”, Pg. 59

[3] Ibid., Pg. 64

[4] De Normandie, Ibid., Pg. 364

[5] Ibid., Pg. 356

[6] Ibid.

[7] Winslow, Ibid., Pg. 105

Radio programme: