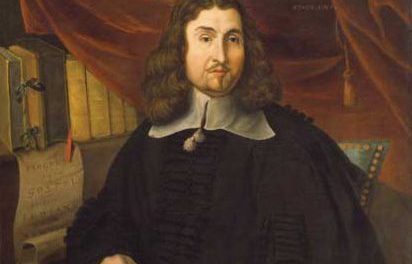

The life of Alexander Henderson begins as one in opposition to the Covenanter and Presbyterian cause in Scotland, but that would later change to the point where he became the most influential Scottish divine in the early years of the Westminster Assembly. Henderson died in 1646, before the Assembly’s work finished in 1653, but his work lived on in the documents of the assembly and those who followed his stand.

What John Knox and Andrew Melville were to the Scottish Reformed movement in the 16th century, Alexander Henderson was to the Second Reformation period in Scotland, from the year 1638 onwards. John Knox’s name is still well-known among the church, but what of Alexander Henderson? Sadly, little to no information exists about Henderson at a mainstream or popular level within the church. Henderson has been largely forgotten, especially when we compare his work with that of Knox.

Early Life

Very little is known of Henderson’s early life. He was born in 1583 in the parish of Creich, Fifeshire, in southwest Scotland. His early education is unknown, but he began University at St. Andrew’s at the age of sixteen. There he studied under Andrew Melville, with James Martin as superintendent there. He learned, as John Aiton described it, “the most profitable and needful parts of the Aristotelian logic and physics.”[1]

It was a Calvinistic humanist education, as he came under the influence of Andrew Melville. His training in Ramist logic, taught by Melville, gave Henderson a clarity, brevity and simplicity which aided his later work involving the National Covenant in 1638, and his production of pamphlets which influence both the Scottish and English. This training was theological and thorough in the latest humanist methods of the day. Melville’s own developments and innovations in education led to the high standard of training found in men preparing for gospel ministry. Henderson even went on to teach rhetoric and philosophy at the college.

Early Ministry

Henderson was Episcopalian in his view of church government. In 1612, Henderson was ordained the minister at Leuchers church. He was placed there by George Gladstone[2], the then Archbishop of St. Andrews. Henderson had high regard for Gladstone at the time.

Henderson’s ministry in Leuchers did not have a happy beginning. Leuchers was hostile to any form of Episcopalianism, so much so they prevented Henderson from entering in through the door by nailing it shut. Henderson eventually found his way into the church building through the window! At the time, sadly, Henderson’s loyalties were more to Gladstone than to his flock in Leuchers.

A few years later, in a nearby village called Forgan, Henderson came to hear the famous Robert Bruce preach. Henderson did not want to be seen so he went into the darkest part of the building. Bruce’s text was John 10:1 which reads:

“Verily, verily, I say unto you, He that entereth not by the door into the sheepfold, but climbeth up some other way, the same is a thief and a robber.”

This text convicted Henderson of his own episode of entering through the window of the church building in Leuchers. He was then converted over to the Presbyterian cause and principles. He saw that it was wrong for the congregation to not be able to call their own minister. He saw that it was wrong for any man to force himself on the congregation. It was from then on a change was seen in the direction of Henderson’s ministry. While his ministry did not have a happy beginning, he became greatly beloved of the congregation at Leuchers.

Presbyterianism vs King James VI of Scotland (James I of England)

In order to see the part Henderson would play after the influence of Robert Bruce’s preaching, we need to consider the battle which was taking place in Scotland before Henderson’s conversion and what led to him becoming the most important man in Scotland by the late 1630s.

During the time of John Knox, Scotland as a nation had entered into covenant with God and had been firmly committed to Presbyterianism. However, near the end of Knox’s life, these convictions began to fade in Scotland. Andrew Melville was a major leader in pointing Scotland back to its covenant commitments and the promotion of Presbyterian church government.

During the time of both Knox and Melville, the battle was over if the church was to be governed by the king, Erastian Episcopalianism, or if the church was to be independent of the state and royal influence, in the form of Presbyterianism.

In 1567 King James VI became the King of Scotland. James was a Protestant, unlike his mother Mary, Queen of Scots, and he supported reformation in Scotland, but not always to the satisfaction of those in favour of Presbyterianism. At times it seemed like James supported Presbyterianism, but it became apparent time and again that he believed in the divine right of kings, and his support was really behind Episcopalianism. This was a great disappointment to many of the Puritans who had hope James would help the Reformation in England, after becoming King James I of England in 1603. James would remain the King of Scotland, England and Ireland until his death in 1625.

Over the course of the reign of King James I, there was a creeping Episcopalian influence across the land, much to annoyance of many of the Scots. This sentiment was seen in the locking out of Alexander Henderson outside of the church in Leuchers. The church in Leuchers rejected Archbishop Gladstone as he replaced the much respected David Black. The circumstances of Mr. Black’s removal from St. Andrew’s showed the influence of this growing Erastianism in the land, as Black was banished to the North for daring to speak against the royal court in 1596. Bishops were also introduced during the time of James’ reign.

The Articles of Perth

In 1618, a few years after Henderson’s conversion to Presbyterian principles, the Articles of Perth were forced on the church in 1618. There were five of these articles which commanded for (1) kneeling at the sacrament, (2) private communion, (3) private baptism, (4) confirmation of children and (5) observance of festivals. These were seen as idolatrous to the Church of Scotland, as the kneeling before the sacrament seems to point to worshipping the elements themselves, and also they rejected popish holy days like Christmas and Easter. This was an attempt to integrate the Church of Scotland with the Episcopal Church in England.

In the Assembly meeting at Perth in August of 1618, Henderson was one of the clerical commissioners to represent his Presbytery. Archbishop John Spotswood, who succeeded George Gladstone, was at the meeting. Spotswood sat in the moderator’s chair. Spotswood was seeking a unanimous agreement with the Five Articles in question. The King’s letter was read out over and over in order to intimidate those in attendance. It was stated that some who refused would be banished and could face other penalties for failure to comply. The question was put to those in attendance, on whether they would consent or not to the Articles? Henderson and others took a stand to oppose the measures.

Henderson and two other ministers continued their opposition to the Articles and were accused of publishing a pamphlet called “Perth Assembly”, in which it was demonstrated that the Articles were inconsistent with the Scriptures. Henderson denied writing the pamphlet. Henderson would however go on to write many pamphlets later in his life, especially after the enforcement by King Charles I of the Book of Canons on the Church from 1636, as he wrote many pamphlets in a clear, concise and persuasive style which allowed his to communicate his point clearly to the ordinary people of the day. Pamphlets played a major part in shaping public opinion at that time, especially in time of such upheaval as was seen in the 17th century in Scotland.

Henderson’s continued rejection of the Articles was seen in the following Synod entry for 6th April, 1619:

“Mr Alexander Henderson has not given the communion according to the prescribed order, not of contempt, as he deponed solemnie, but because he is not yet fullie persuaded of the lawfulness thereof. He is exhorted to strive to obedience and conformitie.”[3]

Remarkably, Henderson and others facing this censure escaped relatively easily. This would change later in Henderson’s life when the risk would increase under Charles I’s disastrous and tyrannical reign.

From this time, until the 1630s, Henderson was not in a major leadership role within the Church of Scotland. Henderson spent those years reading, studying and involvement with the normal duties of his parish at Leuchars. It seems that he worked quiet well with Spotswood during the 1620s, and it was not until the growing tyranny of Charles I that forced him to a place of public prominence to oppose the measures. While he was not a major national figure during this time, as little is known of him during this period, his influence did grow among other ministers. Henderson was part of a growing community of nonconformists, through which Henderson was known nationally for his qualities. It was how he emerged in 1636 as a natural leader among the Covenanters to argue the case against the idolatry of false worship being introduced by Archbishop Laud and King Charles I.

King James I to King Charles I: The Rise of Erastian Tyranny

During the reign of King James VI of Scotland, who would later become James I of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1603, there was the ever increasing rise of Episcopalianism, or the interference of the King in the affairs of the church. English Puritans had hoped that James would help the church in England as they thought he was a Presbyterian by conviction, but James believed in the divine right of kings and that he should be head over the church.

James moved slowly. He would bring in a measure, but would take his time implementing it. Preachers were banished from the land for speaking against the court, but James, and Archbishop Spotswood, knew that there were only so many changes the Scots were willing to put up with. James was a better and more calculating politician that his son, Charles I. Once James I died in 1625, this slow calculating strategy changed in the royal court.

During the reign of Charles, Charles was determined to bring the church in Scotland into uniformity with the episcopal church in England. Unlike his father, Charles wanted the Scottish to immediately enforce the laws that were there. Along with this desire from Charles, and the influence of the new Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633, William Laud, the problems for the Scottish church grew worse. Laud was rash in contrast with Spotswood in Scotland, and he brought into other errors such as Arminianism, much to the annoyance of the Church of Scotland.

Henderson’s leaves Seclusion to promote National Covenant of 1638

Henderson’s natural leadership qualities were spotted by men such as Samuel Rutherford. Rutherford and others saw that he had a clear mind with a good knowledge of the affairs of the day. Henderson was known for being courteous in debate, but he also spoke with an ease and authority. Even though he preferred to live obscurely, not seeking the limelight, he excelled in spontaneous speaking. He was clear and concise which made him extremely persuasive, even to point of gaining respect from his opponents at times.

Then the crisis arrived where Henderson would become the man of the hour, as much as John Knox was during the 16thcentury Reformation in Scotland, and that was when Charles I commanded the use and practise of the Book of Public Service in November 1636. Every parish was directed to obtain two copies of the book before Easter.

Archibald Johnston of Wariston, a man who greatly aided Henderson with the 1638 National Covenant, described the reaction to the news of the Service Book in this way:

“At the beginning thereof there rose such a tumult, such an outcrying, what by the people’s murmuring, mourning, railing, stool-casting as the like was never seen in Scotland, the bishop both after the forenoon sermon was almost trampled under foot, and afternoon …was almost stoned to dead; the dean was forced to cage himself in the steeple”.[4]

The outcry did not deter Charles I, as he continued to demand that the Book of Public Service was enforced. The Scots saw that there was a need to renew the Covenant of 1581. These Covenanters felt as if their back had been put to the wall. They could not accept idolatry in the Lord’s church.

In 1638 many from all classes of society were drawn together in Scotland to sign the National Covenant, a document which bound them to solemn obedience before God to defend true religion. The National Covenant condemned Roman Catholicism and it was a reversal of the Canons of 1636 which caused much distress for many in the land. The document rejected doctrines such as the authority of the pope, the Roman Mass, purgatory, and the violation of the Second Commandment in images or use of relics of the saints.

The National Covenant was drawn up by Alexander Henderson and Archibald Johnston of Warriston. Henderson was very informed on the theological issues at stake, while Warriston’s great strength was in the legal side of the document so that it was conforming to Scottish law. The National Covenant was inaugurated on February 28th, 1638, in the Greyfriar’s churchyard, Edinburgh. While it opposed what King Charles I was trying to do, with his promotion of Erastianism, it did still urge loyalty to the King. The Covenanter movement of that time was careful to stress that what they were doing was in self-defence against an influx of idolatry into the land, not rebellion against the King. L. Charles Jackson stated that both Henderson and Warriston “carefully structured words and phrases in a way that presented their actions not as originating from radicals but from those who were defenders of lawful practice.”[5]

The Glasgow Assembly of 1638

Later that year on June 7th the Marquis of Hamilton arrived in Edinburgh. He was there as the King’s representative, charged with bringing the Scottish people under the rule of the King in matters of the church and what had been laid down in the Book of Canons of 1636. Hamilton and the King wanted the Scottish church to abandon the Covenant as it stood in the way of Charles’ designs over the church. In a letter sent by the King to Hamilton, Charles wrote this:

“I would rather die than yield to those impertinent and damnable demands (as you rightly call them), for it is all one as to yield to be no king in a very short time.”[6]

Through the added pressure, and with God’s Spirit working on the hearts of the Scottish people, there was a greater demand for a free General Assembly of the Scottish Church. Later that year, in 1638, a free General Assembly was called. While the King called the Assembly, with Hamilton acting as the King’s representative, the Royal Commissioner, the King had no intention of letting the Assembly go ahead with its intended business. Hamilton wanted the declinature which arrived from the Bishops to be read before the choice was made of the Moderator for the Assembly. The High Commissioner saw that he did not prevail in his request and protested against the legality of the Assembly as it had no Moderator, in the eyes of Hamilton.

Alexander Henderson was chosen as the Moderator of the Assembly in Glasgow. For many he was an excellent choice as he was well thought of for many years among non-conformists in Scotland. However, there was some hesitation over his choice as Moderator as they feared losing him in debate as he had excellent debating skills.

There was a clear parting of the ways between the desire of the Assembly and that of Hamilton. The King wanted to preserve episcopacy in the church in Scotland, but there was a firm determination among the Assembly to abolish it. During the Assembly, while addressing the Royal Commissioner, Alexander Henderson said the following in his role as Moderator:

“… we are obliged to loyalty and obedience to our king. There is nothing due to kings and princes in matters ecclesiastical…”

“What is ours, let it be given to Caesar, but let God, by whom kings reign, have his own place. Let Christ Jesus, the King of kings, have his own prerogative, by whose grace our king reigneth, and we pray that he may reign long and prosperously over us”.[7]

Henderson was careful in his address to Hamilton to be respectful and recognise the duty they had in submission to rulers, as he pointed to the 5th commandment in the same address. He wanted to point out that Christ was the only king and head of His Church, but that also the Assembly was not casting off the proper role of the civil ruler. However, much suffering was inflicted on the Covenanters, and Henderson was careful to show a submissive spirit when Biblical and not to come across as rebellious. Henderson was gifted in speaking this way, one of the reasons he was so used by God in bring Scotland together in the first place. His influence was of unifying the nation around its sacred duties to Almighty God.

Conflict erupted during the Assembly over the proposed disciplining of the Bishops. The Royal Commissioner opposed the direction of the proceedings as he saw that it would do away with all episcopacy in the Church of Scotland. The Moderator put the question to the Assembly of whether they felt competent as judges of the Bishops. The Commissioner wanted to delay proceedings and asked to have the question deferred. Henderson said this to the Commissioner after repeated attempts to interfere in the Assembly’s dealings and after the threat to withdraw from the Assembly by the Commissioner:

“I wish the contrary, from the bottom of my heart, and that your Grace would continue to favour us with your presence, without obstructing the work and freedom of the Assembly.”[8]

The Commissioner stated in reply that he could no longer continue and he urged the Moderator to dissolve the Assembly. The Assembly did not, Hamilton prayed in the Moderator’s place and dissolved the Assembly with the King’s authority. He then commanded that they ceased from any further proceeding. One of the reasons given for the objection to the further meeting of the Assembly was that, according to the Commissioner, the cited Bishops were being tried by people who were against them. It seems there was a fear of a biased trial.

The meeting reached a crossroads, would the Assembly listen to the King’s orders in this matter to dissolve the meeting, or would they continue? In obedience to their King in Heaven, Jesus Christ, the Assembly continued in its business. Henderson had this to say upon Hamilton’s departure:

“All who are present know how this Assembly was indicted, and what power we allow to our Sovereign in matters ecclesiastic: But though we have acknowledged the power of Christian kings for convening Assemblies, and their power in them, yet that must not derogate from Christ’s right, for he hath given warrant to convocate Assemblies, whether magistrates consent or not.”[9]

It was then that the trial of the Bishops took place, which led to the excommunication of 8 Bishops. The nature of the discipline was not always simply over differences with regard to ecclesiology, but these men were generally wicked and immoral in their conduct. Henderson said the following after the sentence of excommunication was given:

“Since the eight person before-mentioned have declared themselves strangers to the communion of saints, to be without hope of life eternal, and to be slaves of sin: Therefore we the people of God assembled together for this cause, and I as their mouth, In The Name of the Eternal God, and of his Son the Lord Jesus Christ, according to the direction of this Assembly, Do Excommunicate the said eight persons from the participation of the sacraments, from the communion of the visible church and from the prayers of the church, and so long as they continue obstinate, discharges you all, as ye would not be partakers of their vengeance from keeping any religious fellowship with them…”[10]

By the end of the Assembly at Glasgow the infamous Articles of Perth were declared to be unlawful. The Assembly also condemned a number of popish and antichrist errors which were introduced during the years following 1606, which included the Book of Canons, Liturgy, Book of Ordination and the Court of High Commission. Also, all of the corrupt assemblies from 1606 to 1618 were declared null and void by the Glasgow Assembly.

Henderson preached a sermon on Psalm 110:1 known as “The Bishops Doom”.

“The Lord said unto my Lord, Sit thou at my right hand, until I make thine enemies thy footstool.”[11]

This sermon warned the Bishops that if they did not repent, then the Lord’s wrath would overtake them, either in this life or in the world to come.

Having obtained these victories over the enemy in many areas, Henderson gave the following warning to not let these errors back into the Church of Scotland:

“We have cast down the walls of Jericho; let him that rebuildeth them beware of the curse of Hiel the Bethelite.”[12]

Now that Henderson was becoming more influential, and even more crucial to the Covenanter cause, he reluctantly moved from his charge in Leuchars to Edinburgh. Many felt that he needed to be more central to the action and not remain in Leuchars. He then preached at Scotland’s most famous church, St. Giles’. This pulpit which was once occupied by John Knox.

A National Leader in the Midst of National Conflict and Crisis

The decisions made by the General Assembly in 1638 set off a chain of events which lead to war with England. King Charles’ army entered Scotland in 1639 and during that time Henderson was busy writing and distributing pamphlets on the legality and Biblical truth of the Covenanters stand against the King. Henderson was eagar to get across to his English neighbours the nature of conflict was not a rejection of the King, but of self-defence against popery and antichrist false worship. Essentially there was nothing new in the National Covenant of 1638, according to Henderson’s defence, but a further clarification of the role of the King and the freedom of the Church.

So from that belief in that freedom of Christ’s Church he wrote pamphlets like The Instructions for Defensive Arms. In that pamphlet, Henderson called for the defence of the Scottish nation in the midst of the tyranny posed by King Charles I who would not accept defeat to the Covenanters. Henderson saw the relationship between the people and kings as a covenant, in which both sides had obligations toward one another. In Henderson’s view, Kings could not do as they pleased and it was warranted to defend oneself in the midst of such covenant violation. Henderson was clear to state that this was not for private individuals, but in extraordinary cases where the King had become tyrannical against even lower magistrates in the land. In this case in Scotland, the nobles were in support of the Covenanters and of the National Covenant. Henderson used the 5th commandment to prove his point, where duties were from superiors to inferiors and from inferiors to superiors. He also saw the defence in terms of a battle between Christ and Antichrist, the pope of Rome.

Henderson’s influence was now comparable with that of John Knox in the 16th century, as the natural leader of the Covenanting movement and of the nation of Scotland. In the midst of the battles which took place from 1639 to 1640 (called the Bishops’ War), where there were few casualties, Henderson was one of the chief negotiators on the Scottish side. He was chaplain to the Scottish army by this point and negotiated the peace which resulted from the Treaty of Ripon, which was signed by Charles I in the aftermath of the Second Bishops’ War.

As his influence grew, he became the rector of Edinburgh University. His help allowed the raising of money for the University, he established a library and he was instrumental in the hiring of the first professor in Scotland dedicated to Hebrew, Julius Otto. Otto was a Jew from Vienna who converted to Christianity. Henderson urged the hiring of top professors from the continent who were gifted in specialist areas of Biblical learning.

During the years from 1639 to 1641, Charles I attempted to persuade Henderson to be the permanent Moderator of the Assembly, to which Henderson refused. Henderson saw the danger in making the role permanent. Charles wanted to maintain, in any way possible, that he was head over the church and that he got to decide who the Moderator was.

In 1641, the General Assembly met in Edinburgh, with Henderson voted in for another time as moderator, after a period of not taking the role. Henderson was now the Royal Chaplain to Charles I, with a stipend of 4,000 merks.[13] The King came to hear Henderson preach, such was Henderson’s influence, as it continued to grow in Scotland as well as in England. Henderson was even seen as a positive influence on the King’s Sabbath Day keeping while in Scotland. He once privately corrected the King over the issue, as the King was seen on the golf course on the Sabbath Day. Henderson also conducted family worship, morning and evening, in the Royal Palace.

The Westminster Assembly and the Solemn League & Covenant

From 1642, the English Civil War erupted between the Parliament and the King. Both sides wanted the support of the Scots. The Parliamentarians reached out to the Scots for help in the conflict, with the Scots replied expressing their desire to have full Church unity between England and Scotland. The resulting Westminster Assembly, beginning in 1643, along with the Solemn League and Covenant were seen to be solution to the civil war. The Scots sought the blessings of covenant faithfulness which they though would fall on the nation that was faithful to God.

In 1643 both Alexander Henderson and Archibald Johnston of Warriston drafted the Solemn League and Covenant. Henderson was keen to stress this work of Reformation in Scotland, England and Ireland was a work of God, not of man. He hoped that through this covenant, that “Antichrist bondage”[14] would be cast off. The Solemn League was a clear commitment to Presbyterianism in the three kingdoms. The Solemn League stated the following:

“WE, Noblemen, Barons, Knights, Gentlemen, Citizens, Burgesses, Ministers of the Gospel, and Commons of all sorts, in the kingdoms of Scotland, England, and Ireland, by the providence of GOD living under one King, and being of one reformed religion, having before our eyes the glory of GOD, and the advancement of the kingdom of our Lord and Saviour JESUS CHRIST…”

“That we shall in like manner, without respect of persons, endeavour the extirpation of Popery, Prelacy, (that is, church-government by Archbishops, Bishops, their Chancellors, and Commissaries, Deans, Deans and Chapters, Archdeacons, and all other ecclesiastical Officers depending on that hierarchy,) superstition, heresy, schism, profaneness, and whatsoever shall be found to be contrary to sound doctrine and the power of godliness, lest we partake in other men’s sins, and thereby be in danger to receive of their plagues; and that the Lord may be one, and his name one, in the three kingdoms.”

However, while Henderson had set off with hope for blessings upon the three kingdoms, he intimately felt betrayed by his English brothers who signed the covenant. In private letters he expressed sadness in that he felt that they signed the covenant because they only wanted Scottish help against the King, but once they no longer needed their help, they walked away from their Covenant commitments. Henderson was successful in uniting Scotland behind the Covenant of 1638, but was ultimately without the same success south of the border in England where he spent most of his remaining years.

Henderson, along with men like Samuel Rutherford, David Dickson and George Gillespie, was one of the Scottish commissioners to the Westminster Assembly. Henderson made significant contributions in the area of church government, as he defended the Presbyterian view against that of the Independents and the moderate Episcopalians found within the assembly. There were a range of views represented at the Assembly in this area, and sometimes the debates became heated. Henderson felt a great sense of frustration during his years at the Assembly meetings as there was grindingly slow progress and his health was growing worse as time went on. While the debates were heated, Henderson was known for being gentler than the fierier Rutherford and Gillespie.

Henderson was also involved as the sole author of The Directory of Public Worship, or at least as one of the main contributors to the document. The document was influenced largely by his earlier significant work published in 1641 called The Government and Order of the Church of Scotland. This document describes how Presbyterianism functioned in Scotland during the Second Reformation.

Henderson’s Final Days and His Lasting Legacy

Henderson returned to Scotland in 1646, before the Assembly had finished its work. There he died weary from his labours, but also anxious to be with his Lord in Heaven. He never married.

Henderson’s influence was enormous during this period. He had a wonderful unifying effect on the Covenanting movement in his native Scotland. He convinced people of the importance of Covenanting principles, from nobility to common men. Here his earlier training, under the influence of men like Andrew Mellville, and his learning at Leuchars while in the ministry, played a vital part in preparing him for this great work that God had prepared for him. He was respected by friend and foes alike.

Sadly, little is remembered about Henderson in recent years. Far more is remembered about other figures who were less central, which is a shame as Henderson’s example continues to offer so much, if we are willing to listen. Henderson’s example teaches, that even during the greatest trials and hardship, it is possible to strive both for unity among the brethren and for Covenant faithfulness in the land; one does not have to sacrifice one for the other.

[1] John Aiton, The Life and Times of Alexander Henderson, Pg. 88.

[2] Sometimes spelt “Gledstanes”.

[3] John Aiton, Ibid., Pg. 104.

[4] Kenneth D. Macleod, Alexander Henderson, Pg. 12.

[5] L. Charles Jackson, Riots, Revolutions, and the Scottish Covenanters: The Work of Alexander Henderson, Pg. 72.

[6] J.G. Vos, The Scottish Covenanters, Pg. 54.

[7] James Reid, Memoirs of the Westminster Divines, Pg. 300, 301.

[8] Ibid., Pg. 303.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Psalm 110:1

[12] Kenneth D. Macleod, Alexander Henderson, Pg. 23.

[13] The merk was a Scottish silver coin.

[14] L. Charles Jackson, Ibid., Pg. 215.

Bibliography

John Aiton, The Life and Times of Alexander Henderson. [Edinburgh, 1836]

L. Charles Jackson, Riots, Revolutions, and the Scottish Covenanters: The Work of Alexander Henderson. [Reformation Heritage Books, 2015]

J.G. Vos, The Scottish Covenanters: Their Origins, History and Distinctive Doctrines. [Blue Banner Productions, 2018]

Kenneth D. Macleod, Alexander Henderson. [Scottish Reformation Society, 2014]

James Reid, Memoirs of the Westminster Divines. [Banner of Truth, 1982]