Introduction

The thought of works being needed for salvation may seem foreign to some today, but on what basis was Adam promised eternal life in the garden of Eden? Was there a difference before the fall of mankind in Adam, or was it by grace as it is today through the saving work of Christ? How does any of this impact how we may view the gospel of Christ, if at all?

This paper aims to look at these questions relating to what some call the ‘Adamic Administration’.[1]Often Genesis chapters 1-3 are often treated purely in terms of the origin of the universe and debates relating to evolution and creation, but is there more we can learn? Are there things we can learn from the Adamic Administration which can help form a bulwark in our understanding of the covenant of grace?

The Reformed View

The Westminster Confession of Faith (WCF) deals with this issue under chapter 7 of the confession, called “Of God’s Covenant with Man” which states:

“The first covenant made with man was a covenant of works, wherein life was promised to Adam; and in him to his posterity, upon condition of perfect and personal obedience.”[2]

The WCF gives the most common Reformed view. This does not mean all the 16th century and 17th century reformers held the view as found in the confession, or even used the term ‘covenant of works’, but it is the most common view. The Reformed view is that in the garden of Eden eternal life was promised to Adam, and those whom he represented as their federal head or representative, if he obeyed God perfectly. Adam was the federal head of the whole human race, and when Adam sinned, we all sinned in him.[3]Adam was in our place before God, and so when Adam sinned, all of mankind sinned in him.[4]

Adam was sinless and processed an original righteousness.[5]While we may sinfully wonder why this is fair, let us consider who would be better suited to obey God perfectly, you or a sinless Adam? Even a sinless, though mutable, man like Adam did fall into sin, how could we possible do any better? We have been born in trespasses and sins. We would have done no better than Adam as we are sinners by nature.

Historically, the covenant of works has also at times been called the covenant of nature. This is due to fact that from nature, man owes God perfect personal obedience. There has been a nervousness with some to use the term ‘work’ in describing any covenant relationship with God, but the term has biblical support. If it does not, then the concept needs to be abandoned.

Key Texts of Scripture

Our final authority cannot be the confession of faith or Reformed tradition, but the infallible and inerrant Word of God. Does God’s Word support the concept of a covenant of works before the fall of mankind in Adam? In our examination of the evidence we will look at two key passages – Genesis 2:15-17 and Romans 5:12-14.

- Genesis 2:15-17

“Then the Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to tend and keep it. And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, “Of every tree of the garden you may freely eat; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.”[6]

Adam was placed in the garden and given responsibilities to keep the garden. By virtue of him being created in God’s image, Adam was required to obey God. Man is expected to keep God’s law and imitate God.[7]This is the same as today, in that we are to follow God’s law, which is written on our hearts.[8]That image of God may be defaced and corrupted, but we still are image bearers of God, even if we may suppress that truth.[9]

In addition to this, God graciously enters into a covenant with Adam. Adam is promised life upon obedience, but promised death upon disobedience of God’s law. The visible sign and seal of this disobedience was the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. By man partaking of this fruit, he was visibly or outwardly in rebellion to God and His law.[10]God owes man nothing, even before the fall when man had not fallen. God is the creator and we are mere creatures. But God by “some voluntary condescension”[11]was pleased to enter into covenant with man who had been created upright and with an original righteousness.

The presence of the tree of life in the garden is also significant, as a visible sign and seal of God’s favour toward them.[12]Something which they later lost after Adam fell into sin.[13]The presence of this tree in the garden pointed towards that they had life, but once they sinned they died.[14]

We can see that man was promised life upon obedience to God, but also promised death once Adam broke the covenant. This is why the covenant in the garden has been generally referred to as a ‘covenant of works’, as it distinguishes it from the covenant of grace. The covenant of grace comes in once mankind can no longer have a relationship with God if their perfect personal obedience is something required of them. Any relationship after the fall must be different due to the nature of sinful men.

Man after the fall is not like Adam before the fall. Adam was upright and was capable of obeying God (posse non peccare), but was also capable of sinning (posse peccare). While man after the fall is incapable of not sinning (non posse non peccare).[15] So any relationship between God and fallen sinners will have to be based on the perfect obedience of another in their place, as no relationship of this kind could last. Otherwise, its foundation would be unstable. It must depend on the perfect obedience of another who can obey that law perfectly, that is Christ, who is the second Adam.

2. Romans 5:12-14

“Therefore, just as through one man sin entered the world, and death through sin, and thus death spread to all men, because all sinned— For until the law sin was in the world, but sin is not imputed when there is no law. Nevertheless death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those who had not sinned according to the likeness of the transgression of Adam, who is a type of Him who was to come.”

This text, written under the inspiration of God by the Apostle Paul, gives further insight into what happen in Adam when he sinned, by partaking of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.[16]Sin entered by ‘one man’, that is Adam. Adam was not the first to sin, as Eve was first to sin, but there was something more significant about Adam’s sin.[17]This was because Adam was the federal head of all mankind, not Eve. By ‘one man’, as we see in our text, sin entered in, and this ‘one man’ is undoubtedly Adam.

‘[D]eath spread to all men, because all sinned’ in Romans 5:12 shows that Adam’s sin was seen as our sin. This is because Adam was our representative in our stead. His sin was our sin, and his death also became ours. This law that was broken is referring to the moral law, not just the negative prohibition of the eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. We know this as Paul wrote that ‘death reigned from Adam to Moses’ even though we did not yet have the ceremonial laws added at Mount Sinai. Man was also driven out from the garden, so there remained at this time no probation to not eat of a particular tree. So then how could death reign before Moses? Because men were in Adam and they sinned against the law of God written on their hearts, however much that image has been defaced by the fall.

It is also important to point out that in this period until Moses, men did not die because they merely imitated Adam, but because they were now under the wrath of God.[18]They were by nature children of wrath.[19]Because of this one sin of Adam, they were born sinners. These and other features show that Adam represented mankind in the garden, and why this one sin of Adam differs from all the others which followed after the fall.

Also we learn from Romans 5:14 that Adam was ‘a type of Him who was to come’. There is a connection between Adam and the second Adam, Christ. Both represent a group of people. Those in Adam are represented by Adam, who broke the covenant and are still trusting in their righteous deeds to obtain eternal life.[20]But those in Christ are represented by the one who obeyed the law perfectly, and who also bore the punishment their covenant-breaking deserved.[21]

Is the Adamic Administration a Covenant?

While the most common view within the Reformed community has been that of a covenant of works, there have been some who have objected to the term, and others who have rejected the concept entirely.[22]

It is important to remember that the covenant of works was not emphasised or seen in explicit language by all those who were orthodox or Reformed in the past. John Calvin himself made no mention on the covenant of works, but was of course orthodox in his law and gospel distinctive in expositing other parts of the scriptures. A clear distinction between a pre-fall covenant and post-fall covenant was not expressed until Zacharias Ursinus, who was an author of the Heidelberg Catechism.[23]

With that said, it does not mean that rejection of the term, and even the concept of some kind ‘merit’ in covenant before the fall, has no bearing on how we may see the gospel. Understanding where Adam failed can give us a fuller picture of where Christ succeeded and cause us to be more in awe of what Jesus Christ did for us while we were yet sinners.[24]

The term of ‘covenant’ was rejected by the respected and influential Reformed theologian John Murray. Murray challenge the concept of there really being a covenant in the garden of Eden when he said:

“It is not designated a covenant in Scripture… Scripture, always uses the term covenant, when applied God’s administration to men …”[25]

The main thrust of his argument is that the term covenant must be used in order to be deemed so. However, it does not affect how he sees the condition of life as obedience.[26]

Let us now examine Murray’s claim. Does the word of a concept need to be used in order to justify using the said term? If so one would have to reject the idea of the Trinity, as the term is not used in the scriptures either, but through good and necessary consequences we should examine the text of scripture to see if the concept is there.[27]Are the characteristics of covenant found in the garden of Eden prior to the fall of man?

So what are these characteristics? A covenant is something that involves curses, promises and some sort of agreement. The Hebrew word for ‘covenant’ בְּרִית(berith) implies a relationship between an inferior and a superior. Some covenants are monopleuric or unilateral in nature and in a sense do not wait for a response from man. Man is simply given the conditions. Upon examination of the covenant in the garden of Eden, the relationship between God and man seems to fulfil all these criteria. Not all covenants are the same. Some covenants are there, but the word ‘covenant’ is sometimes not used, at least initially. This can be seen in the Lord’s covenant with day and night which is most certainly unilateral:

“Thus says the Lord: ‘If you can break My covenant with the day and My covenant with the night, so that there will not be day and night in their season, then My covenant may also be broken with David My servant, so that he shall not have a son to reign on his throne, and with the Levites, the priests, My ministers.” –Jeremiah 33:20-21

No mention of the formation of this covenant with day and night is made in the creation account given in the book of Genesis. Like other covenants, the covenant of works involves a curse upon breaking of the covenant, a promise of eternal life upon perfect personal obedience to God, and the covenant is clearly unilateral from God, as superior, upon Adam, as inferior. Therefore, upon examination of the typical characteristics of a covenant, the rejection of the term, based upon the argumentation of the word being necessary, seems misguided at best.

Hosea 6:7 is also mentioned by Murray. Murray rejects the use of the text to support the covenant of works when he stated:

“Hosea 6:7 may be interpreted otherwise and does not provide the basis for such for such a construction of the Adamic economy.”[28]

This is a much debated text which is often used to support the idea of a covenant in the garden of Eden. It is easy to see the appeal of such an argument as it seems to close the door to any rejection of the covenant of works.

“But like]men [כְּאָדָ֖ם-kə·’ā·ḏām] they transgressed the covenant;

There they dealt treacherously with Me.” –Hosea 6:7

The Hebrew word, translated here ‘men’, can also be translated ‘Adam’. Arguments can be made for both renderings, but in the context of the whole Bible, with what has gone before, ‘Adam’ seems to make a lot of sense here. Even if ‘men’ is used, it could still be argued that as all mankind was in Adam so it equally points to the covenant of works, as much as the ‘Adam’ rendering. ‘Adam’ makes the reference clearer and leaves out any ambiguity of what the reference is pointing to.

Merit and the Covenant of Works

Great difficulty comes when critiquing John Murray’s view, as it is somewhat unique. Definitions of grace, and its antithesis works, can often get lost. This is in no small part due to controversies that have arisen due to the rejection of the covenant of works in recent times. Certain movements, such as the New Perspective on Paul (NPP) and the Federal Vision (FV) fall within this category. But we need to realise that Westminster Confession of Faith recognised a gracious nature to the covenant of work when it used the words ‘voluntary condescension.’[29]

For some, the following quote from John Murray might seem like a compromise in the direction of NPP and FV:

“From the promise of the Adamic Administration we must dissociate all notions of meritorious reward. The promise of confirmed integrity and blessedness was one annexed to an obedience that Adam owed and, therefore, was a promise of grace.”[30]

In the context in which we live one can certainly sympathise with someone getting nervous with such a statement, but it really does not deserve such an evaluation.

J.V. Fesko, an able critique of the NPP and FV movements, had some concern over Murray’s comments:

“This means that Adam’s presence in the garden was based upon a mixture of grace and merit – he had to be obedient but the results of this obedience would have been rewarded on the basis of grace rather than justice.”[31]

This is where the difficulty comes in. In what way was the covenant gracious, and in what way was it meritorious? Do, or can, the two really mix?

To get a sense of what Murray means, let us go back to the beginning and ask the question, what does God owe anyone? Even if they are sinless and righteous, what does God need to do for these people? Does God in any way, in the very nature of His being, owe men eternal life and blessedness in His presence forever? Can a mere creature, dependent on God, even without sin, demand anything? Of course, the answer must be no.

So this is where the ‘voluntary condescension’ of the WCF comes into play. The covenant of works was set up initially, with the terms of obedience and cursing, by grace. Not the same as God showing mercy to lost sinner saved by grace, but in no ‘strict’ sense can we merit anything from God. God must graciously come down to us to set these terms in place. Is there a ‘merit’ in Adam’s obedience? Does God have to grant eternal life if Adam obeys perfectly for a certain duration? Yes, God does, but only because God graciously promised to do so. As Murray wrote:

“God is debtor to his own faithfulness.”[32]

So there is debt within the covenant, and not grace, even in Murray’s formulation. Murray’s reference to grace does not necessitate for it to be mixed with works within the covenant. However, when in coming to go into covenant with Adam, God does so graciously. Now, due to the stipulations set out by God in the covenant, man can by his own works obtain salvation within the covenant of works in Eden. Therefore, within that covenant in Eden, man could in a limited sense ‘earn’ or ‘merit’ eternal life. There is nothing in Murray’s writing on the Adamic Administration to suggest that he rejects this formulation.

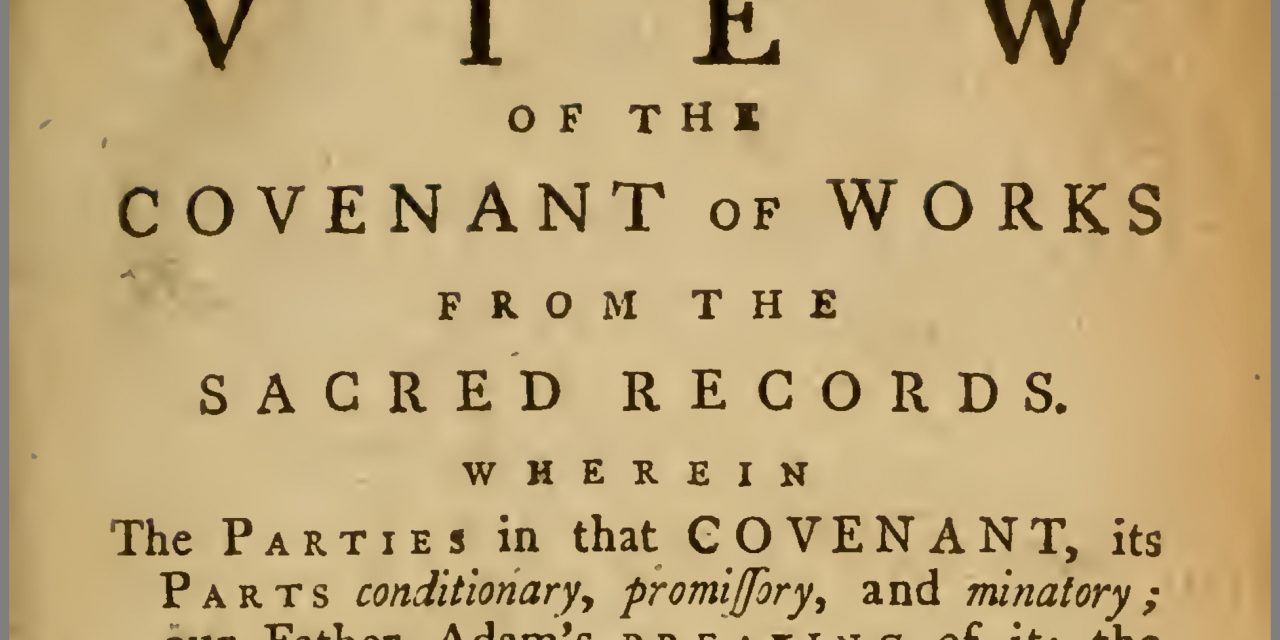

Is this the first time this has been seen? Consider John Ball, a 17thcentury Presbyterian minister of the gospel, who wrote a classic work on the topic of the covenant of grace, called ‘A Treatise of the Covenant of Grace’. The work was published in 1645, after Ball had passed away. John Ball was a major influence on the Westminster Confession of Faith. Ball wrote about the idea of merit when it comes to the covenant of works, and here is what he wrote:

“In this state and condition Adam’s obedience should have been rewarded in justice, but could not have merited that reward.”

Ball also commented that:

“[I]t is impossible the creature should merit of the Creator, because when he hath done all that he can, he is an unprofitable servant, he hath done but his duty.”[33]

This can a difficult exercise at times, as on one hand we can maintain that God does not owe us anything purely because of who we are, even if we were holy, but he also owes those who fulfil the covenant of works due to the covenant itself. So there is a gracious element in the establishing of the covenant of works, but within the covenant reward of eternal life is based on the performance of Adam. We must make sure not to add grace within the covenant as it can flatten out our distinctions between the pre-fall covenant of works, and the post-fall covenant of grace. The first pre-fall covenant is conditioned on the work of Adam, the second is conditioned on the work of the second Adam, who is Christ.

As Cornelis P. Venema stated, Murray’s difference with the Westminster Confession of Faith is ‘partially terminological.’[34]For this reason we must approach with caution when we critique someone who rejects the covenant of works and carefully examine how they use the terms ‘merit’ and ‘grace’. We must seek to understand what they mean by the terms, of God entering into covenant with man, or in the sense of within the stipulations of the covenant once entered into? This is certainly an area where it is easy to misunderstand what the author intending by using terms like ‘merit’ and ‘grace’ in regards to the covenant of works in the garden of Eden.

Some authors like J.V. Fesko[35]and Meredith Kline[36]have argued ‘a merit’ in terms of strict justice with no reference to a gracious element. The fear is it will affect the understanding of the second covenant of grace and merit procured by Christ. There is no need for this fear as long as we make sure that the basis needed for both covenants is the perfect obedience, and not partial obedience, of a federal representative. Both covenants can be said to be graciously entered into by God, but it does not alter the substance of these covenants. One covenant is of works and the other is of grace. The covenants differ in substance. They differ in what they seek from man.

Dangers in Rejecting the Covenant of Works

Are there dangers in stating or believing that there is no covenant of works? Do we really need to keep a clear demarcation between the covenant of works and the covenant of grace? After all, do they not have similar gracious elements involved in how God really owes nothing to any form of obedience? If we reject the covenant of works, and really almost blend it in with the post-fall covenant of grace, then the consequences can be dire. While it is possible to reject the covenant of works and remain faithful to the gospel, possibly in an inconsistent matter at times, but there exists tragic examples of rejecting a dual-covenantal framework for a mono-covenantal framework which denies the central truths of the gospel.

How are the two covenants different? The covenants are different in substance. The covenant of works demands obedience and promises a curse on disobedience, while the covenant of grace demands repentance and faith toward Christ, which themselves are graciously granted to the elect in Christ upon conversion.[37]Man naturally is dead in sin and cannot respond in faith to the gospel, as he is a slave to sin.[38]

Wilhelmus àBrakel stated the following on the importance of understanding the covenant of works:

“Whoever errs here or denies the existence of the covenant of works will not understand the covenant of grace, and will readily err concerning the mediatorship of the Lord Jesus Christ. Such a person will very readily deny that Christ by His active obedience has merited a right to eternal life for the elect.”[39]

As we now deal with the term ‘merit’, we do so within the covenants as established by God himself. There must be some sense in which Adam ‘merits’ eternal life if he keeps the covenant of works by obeying God’s commandments. There is a direct connection between Adam and Christ, as seen in Romans 5:12-19, which has Jesus Christ as the second Adam. If Adam cannot merit life, then how can Christ, on behalf of his people chosen before the foundation of the world, do so?

In order to have a right relationship with God, we need a positive righteousness, not just a blank slate with our sins washed away, as essential as that is. Romans 1:17 tells us that the ‘just’ shall live by faith. How can we be just before God? We need to keep the law of God perfectly, but we cannot (non posse non peccare) and have not. So, we need a substitute. We need another to stand in our place.[40]

Historically, due to past theological disputes, two aspects of Christ’s obedience have been identified, which are His active and passive obedience. Active obedience is the sense that He kept the whole law throughout His whole life on this earth.[41]His passive obedience is often misunderstood as meaning that Christ was somehow passive, but this confusion is more due to the change in our English language over the centuries. The word essentially means ‘suffering’, in how he bore the wrath and satisfied the penalty due to His people. They are essentially one obedience, not two, but some deny the active part of Christ’s obedience, so the distinction becomes necessary to help prevent error.

If the covenant of works is rejected, or changed to be just simply the covenant of grace in the garden of Eden pre-fall, or if the sense in which Adam had to obey in order to be rewarded eternal life is watered down somehow, it could lead to a situation where both grace and works are included inseparably together within that one single covenant. By faith alone, some could now mean ‘faithfulness’, but this faithfulness includes works, rather than excludes works, as it should. Grace and works, like oil and water, do not mix in the scriptures.[42]This is why it is essential that we do not mix them together and keep the covenants apart. If grace is mixed into the covenant of works, this means perfect personal obedience is not needed as some grace will make up the shortfall. If then, what is received in Christ is a partial obedience (as Christ is the second Adam), or an obedience which is not enough to be perfectly just, then something else is needed to make up that shortfall. This sadly is the kind of logic, sometimes seen within the modern church, which can affect how people view and teach the very gospel itself.

The confusion over this issue can affect any teaching every time there is a reference to the law or indeed faith. If Adam’s obedience was not a perfect obedience, apart from grace, then was Christ’s? And if so is it enough for us sinners? Do we need to fulfil a certain standard after conversion to meet these covenantal standards, if the distinction between the pre-fall and post-fall covenants are destroyed? Can we obey God like Adam did, thereby opening an avenue to providing our own active obedience rather than which is from Christ alone?

Why does it Potentially Affect the Gospel?

Many evangelicals today simply see the command to not eat of the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil, and think no further on the issue. They continue to see salvation as a work of grace from beginning to end in any context, pre or post-fall. However, some who have rejected the idea of the covenant of works have taken it further. Again, in such a formulation there is really only one covenant, and not two, as taught in the Westminster Confession of Faith. If there is only one covenant, as some are now teaching, then the obedience required by Adam was also partially by faith. Then in the covenant of grace, when the Bible says believe, according to this distortion of the gospel, really means to have faith and to have works. As in this view, the covenant requires something from us, as it did in Adam, which will affect the understanding of justification by faith alone. Now justification, by following such logic, becomes partially by faith and also by works.

It is important to see that the covenant of works requires obedience, while the covenant of grace requires faith alone in Christ alone. J.V. Fesko wrote:

“In a prefall world, therefore, Adam would be justified by his works.”[43]

If they become flattened out, it can corrupt our understanding of the gospel and of the work of Christ. The active obedience of Christ, the law keeping required of us, or to be positively righteous before God, would no longer be something purely from Christ (if at all), but could be provided from us as works would be demanded by the covenant under this understanding. Some would also contend in defence of this view, that if the pre-fall covenant was gracious, and therefore not meritorious, then these works required of the post-fall covenant are not meritorious either.

Covenantal Nomism

In recent times a new movement called the New Perspective on Paul (NPP) has emerged based on such ideas. Men like E.P. Sanders, James Dunn and N.T. Wright have taught that first century Judaism did not teach legalism as had previously been believed in the church. Therefore, what Paul was refuting in his writings was not legalism, but rather what Paul was refuting was that the ‘works of the law’, or the badges if the covenant as they see it, saved. Essentially they were refuting salvation by external covenantal markers. As Sanders summarised:

“In short, this is what Paul finds wrong in Judaism: it is not Christianity.”[44]

Robert J. Cara comments on the difference between Sanders’ view and that of the Reformed system:

“[T]he Reformed system clearly distinguishes between works done as part of the Covenant of Works (legalistic works) and works done as part of the Covenant of Grace. Sanders tends to confuse the two.”[45]

The NPP teaches that works are non-meritorious and therefore it is all of grace.[46]N.T. Wright gave another summary of this view of the covenant when he said:

“The Jew keeps the law out of gratitude, as the proper response to grace – not, in other words, in order to get into the covenant people, but to stay in.”[47]

This view, called ‘covenantal nomism’ by Sanders, fundamentally misunderstands the nature of works, and how they are antithetical to grace. The initial part of salvation is by grace alone, however, according to the NPP, works are required to maintain our standing before God. Good works are necessary to salvation in one sense, and that is that they are a necessary fruit of salvation. However, they are not an instrument of salvation. Faith is the alone instrument of salvation in the covenant of grace.

Norman Shepherd, a former professor at Westminster Theological Seminary, rejected the covenant of works. He stated:

“God never required his image bearers to earn eternal life by the merit of their good works.”[48]

After a lengthy controversy over Shepherd’s teachings, the Board at Westminster Seminary said the following to defend their dismissal of Shepherd from the seminary:

“Mr. Shepherd rejects not only the term ‘covenant of works’ but the possibility of any merit or reward attaching to the obedience of Adam in the creation covenant. He holds that faithful obedience is the condition of all covenants in contrast to the distinction made in the Westminster Confession…The covenant of works was conditioned upon perfect, personal obedience. The covenant of grace provides the obedience of Jesus Christ and therefore does not have our obedience as its condition but requires only faith in Christ to meet the demand of God’s righteousness.”[49]

What did Shepherd teach? Did his rejection of the covenant of works impact his view of the gospel of grace? During the controversy over Norman Shepherd’s views, which took place in the 1970s in Westminster Theology Seminary, Shepherd submitted a paper on his views called ‘Thirty-four Theses on Justification in Relation to Faith, Repentance, and Good Works’. In it he said the following in Thesis 22:

“The righteousness of Jesus Christ ever remains the exclusive ground of the believer’s justification, but the personal godliness of the believer is also necessary for his justification in the judgment of the last day (Matthew 7:21-23; 25:31-46; Hebrews 12:14).”[50]

Just like E.P. Sanders, Shepherd was confusing works in the covenant of works with those good works produced by someone regenerated within the covenant of grace. Prior to these theses, Shepherd was also teaching that justification was by faith and by works. Sadly, while many do not go in this direction, some do end up corrupting the gospel itself with their rejection of the covenant of works.

Conclusion

Much more could be said on this often overlooked topic. One must caution against any overemphasis on any doctrine. One can understand the doctrine of the covenant of works, and still be wrong on the gospel. There are various ways for legalism, and antinomianism,to enter the church, to enter our pulpits, to enter our lives, and to enter our homes. We must guard against false views, but at the same time, not dismissing those with whom we may disagree on issues not directly affecting the gospel and our confessional stance regarding the creed we profess to believe.

A proper understanding of the covenant of works can be a major positive to our understanding of the work of Christ while on this earth, and how he was the second Adam to come to succeed where the first Adam failed. When we understand these things better, we will, by God’s grace, be filled with more gratitude and joy for what God has done. This doctrine of the covenant of works has great practical and pastoral value.

Once we can see that to even try to earn God’s favour by our efforts, then we can understand that this is to place ourselves under the first Adam again. It is to place ourselves under a broken covenant. It is to place ourselves under God’s displeasure. We cannot please God in ourselves, but God is well pleased with His Son.[51]Once we understand we cannot please God, and that pleasing Him through the first Adam is impossible, then we are free to serve Him out of gratitude.

This gratitude is expressed in good works which are produced by someone who is born again by the Spirit of God.[52]We do not cast aside good works in the covenant of grace, but we see what they are. They are there as evidence that someone is born again. They are there to glorify our God in heaven. They are not there is earn our favour before God, either in our justification now, or on the last day. The first Adam failed, in whom all will die, but in Christ, our second Adam, we will live because of His perfect obedience to the law, and His baring of the wrath of the broken first covenant.

May the Lord grant His people knowledge of what good works are, and may His people be delivered from the leaven of legalism so they can serve Him in true freedom and joy.

[1]John Murray, Collected Writings, 2:47

[2]Westminster Confession of Faith, Chapter 7:2

[3]1 Corinthians 15:22

[4]Romans 5:12-14

[5]Ecclesiastes 7:29

[6]NKJV Translation.

[7]Ephesians 5:1

[8]Romans 2:14-15

[9]Romans 1:18-20

[10]James 2:10

[11]WCF 7:1

[12]Genesis 2:9

[13]Genesis 3:22-24

[14]Ephesians 2:1

[15]1 John 1:8

[16]Genesis 3:6-7

[17]1 Timothy 2:14

[18]John 3:36

[19]Ephesians 2:3

[20]Isaiah 64:6

[21]Romans 8:3

[22]O. Palmer Robertson, The Current Justification Controversy, Pg. 77. Norman Shepherd is one such example but his views would not be seen as Reformed or orthodox in many areas.

[23]Cornelis P. Venema, Christ and Covenant Theology, 4.

[24]Romans 5:8

[25]John Murray, Collected Writings, 2:49.

[26]Ibid., Pg. 51

[27]WCF 1:6

[28]Murray, Ibid.

[29]WCF 7:1

[30]Murray, Collected Writings, 2:56.

[31]J.V. Fesko, Justification: Understanding the Classic Reformed Doctrine, 129.

[32]Murray, Ibid.

[33]John Ball, A Treatise of the Covenant of Grace, 1645 Edition, 10.

[34]Cornelis P. Venema, Christ and Covenant Theology, 20.

[35]Fesko, Justification, 131.

[36]Venema, Ibid., 72.

[37]2 Timothy 2:25

[38]Romans 6:17

[39]Wilhelmus àBrakel, The Christian’s Reasonable Service, 1:355.

[40]Isaiah 53:6

[41]Matthew 5:17

[42]Romans 11:6

[43]J.V. Fesko, Justification, 134.

[44]E. P. Sanders, Paul and Palestinian Judaism, 550-552.

[45]Robert J. Cara, Cracking the Foundation of the New Perspective on Paul: Covenantal Nomism versus Reformed Covenantal Theology, 67.

[46]Fesko, Ibid., 168-169.

[47]N. T. Wright, What Saint Paul Really Said, 246-247.

[48]R. Scott Clark (Ed.), Covenant, Justification, and Pastoral Ministry, 51.

[49]O. Palmer Robertson, The Current Justification Controversy, 77.

[50]O. Palmer Robertson, Ibid., 35.

[51]Mark 1:11

[52]Matthew 3:10; 7:16-17